In the podcast (via Sprogcast) linked below, Heather Trickey draws on her current PhD research, and her research and voluntary work for the National Childbirth Trust (NCT) to reflect on peer support and infant feeding policy. Heather is a Research Associate based in DECIPHer, a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence based at Cardiff and Bristol Universities. Heather’s PhD research is joint funded by the Medical Research Council and the National Childbirth Trust.

Listen In – Podcast

Author: Heather Trickey

Click here to listen to the podcast, and hear a few thoughts on infant feeding policy and the potential of breastfeeding peer support. The interview follows a presentation I gave at the Association of Breastfeeding Mothers (ABM) Annual Conference 2016. You may notice some background noise, including contributions from several babies in attendance!

Continue reading for a selection of slides from my talk, a little background to my thinking, and some afterthoughts.

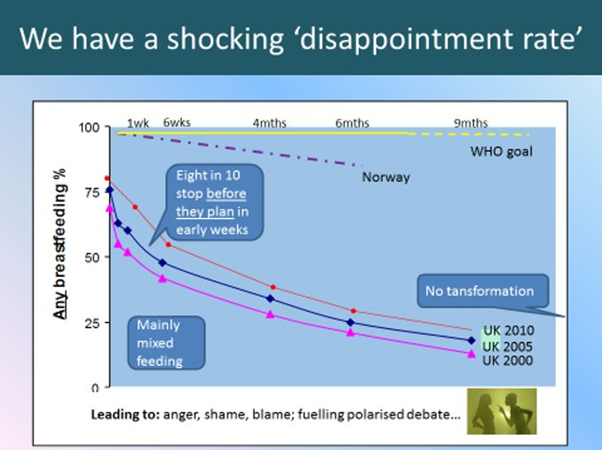

Our breastfeeding disappointment rate

By international comparison (including in comparison to other English speaking nations) few mothers living in the UK breastfeed for long. Our rates are strongly patterned, socially and geographically, with less advantaged mothers and those living in less wealthy areas, being less likely to start by breastfeeding, and less likely to continue. For more than one in four UK mothers, breastfeeding just isn’t a sufficiently attractive option to attempt, even once. Furthermore, as NCT (the UK’s largest charity for expectant and new parents) points out, ‘mothers experience unacceptable levels of pressure however they feed their babies’ and ‘a high proportion of mothers who start breastfeeding stop before they want to, often in the early days’. In fact, the last infant feeding survey found that, every year, around a quarter of mothers who give birth start and then stop breastfeeding in the first six weeks, with eight in ten mothers stopping before they planned. This steep ‘drop-off’ is illustrated below in Slide 1.

Slide 1: UK trends, and the WHO goal.

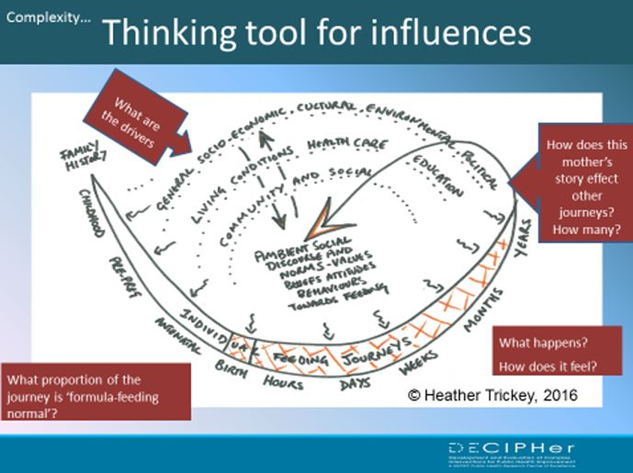

Our feeding journeys

I have never met a mother whose feeding story did not make sense in its own narrative context. Sometimes, breastfeeding comes relatively easy – feels natural, often beautiful. Sometimes there are challenges to overcome. For some of us, breastfeeding just seems inconceivable, ‘not for me,’ incompatible with family circumstances and competing priorities. Often we plan to breastfeed, but the baby won’t latch, or we find that we run out of milk – and perhaps now (unbelievable!) we feel the experts are shaming us for that.

If we draw back the lens and place these stories within their broader social context, we see how our own journeys form part of broader geographical and social patterning. At six months, 80% of Norwegian mothers are breastfeeding compared to only around 25% of mothers in the UK (most of whom are also giving formula). It’s clear that our different experiences are not a simple question of biology. Whether we are aware of them or not, our personal decisions involve a complex mix of bio-psycho-social processes and conditions – our wider ecological context. Furthermore, our decisions are not one-off. We have to make it up as we go along and ‘what we do next’ must respond to our past and current experience and circumstances.

This patterning must challenge our ideas about ‘choice’ – making and sustaining a decision to breastfeed is easier in some contexts than in others (Slide 2).

Slide 2: Thinking ecologically – and dynamically – about feeding decisions

Ecological infant feeding policy

The case for taking an ecological approach to breastfeeding policy is longstanding. A recognition that mothers’ decisions should be considered in terms of family, community, health service, education, workplace and wider cultural context, and especially in the context of intensive and often unethical formula marketing, underpins the WHO Global Strategy on infant feeding and is set out in UK NICE evidence into practice briefings. In 2011, NCT updated its infant feeding policy, affirming an intention to support all mothers along their feeding journeys while promoting and protecting ‘the conditions that make decisions to breastfeed more straightforward’; in other words, to look beyond individual-level health education approaches, which can leave mothers ‘exhorted but not supported’ to breastfeed.

A 2016 Lancet series of articles on breastfeeding and public health re-enforces the message that we cannot expect to achieve shifts in the breastfeeding rate, or to achieve consequent health gains, if the focus of public health attention remains on educating expectant mothers. This evidence forms the basis for UNICEF UK’s recent Call for Action, highlighting the need for the UK governments to take a strategic approach to infant feeding policy and to provide a firmer pushback against competing commercial interests.

Despite this consensus, over the past ten years the primary UK policy focus has been on making (much needed) changes within the health service through implementation of UNICEF Baby Friendly standards.

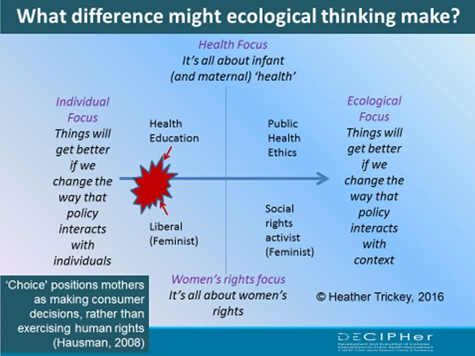

Breastfeeding rates and a woman’s right to choose

In this interview (and in the talk that prompted it) I suggest that a health service and health outcome’s focus on infant feeding decisions may be inadvertently sidelining long-standing rights-based perspectives. A rights-based persepective prioritises women’s experiences of feeding and maternal autonomy; priorities which are the foundation for many mother-to-mother support organisations including NCT. A health policy discourse will have an incomplete fit with these wider social and personal concerns. Peer supporters – or, we could loosen our terminology to simply include all mothers – are motivated by rather more than disease prevention.

I have discussed the evidence for peer support here and here, arguing that experimental studies are frequently based on delivery models in which peer support is seen as a way to improve the health care pathway for individual mothers. This view of peer supporters as paraprofessionals and support workers risks sidelining the potential of mother-to-mother support and fails to engage with volunteers’ interest in challenging and changing the wider support and social context for breastfeeding. When we broaden our thinking about what peer supporters do we see that peer support may be an under-tapped (and under-evaluated) lever for change. Furthermore, joining the dots between a health promotion agenda and a broader social rights agenda –shifting the weight of responsibility for change from individual mothers – may help to facilitate less divisive context for infant feeding policy (Slide 3).

Slide 3: Caution, positions highly simplified! – what difference can ecological thinking make?

Afterword

I wasn’t expecting to be interviewed, sometimes you can almost hear the gears turning as I speak … three points of afterword:

First, the ABM context explains my focus on the role of peer supporters and on the role of the voluntary sector more generally. Of course, an ecological approach has implications for all sectors.

Second, I should explain why I used the example of Merthyr Tydfil as a town where community level social norms favour formula feeding. I was referring to findings from recent community insights research which indicate discomfort with breastfeeding when out-and-about was an important barrier to breastfeeding in Merthyr. The research team worked with local mothers to understand the potential role of peer support in changing the context.

Finally, were I giving the interview again, I’d be clearer that an ecological approach does not exclude health education. Furthermore, from a rights perspective, access to reliable, evidence-based public health information is potentially empowering. The majority of mothers do now receive some advisory health information, in gist at least, thanks to changes in health care practice and to Baby Friendly. My point – that health education can be counterproductive if it is delivered in a context in which mothers face insurmountable barriers to taking up advice and if the advice itself fails to acknowledge that ultimately mothers themselves are best placed to make decisions that are right for themselves and their families. We are seeing a growing consensus that public health policy needs to make a strategic shift of emphasis towards facilitating a more enabling context for decisions to breastfeed, whilst supporting all mothers along their feeding journeys. Perhaps we can begin to change the conversation. But in order to operationalise an ecological and rights-based understanding infant feeding policy will need to step outside of the health service and address broader societal constraints. Strategic action as well as good words will be required.

UNICEF UK are calling for a change in the conversation about infant feeding. To add your voice, please visit the following link.

For more information on Heather’s study, please contact her via email at TrickeyHJ@cardiff.ac.uk.

Featured image courtesy of John Finn, Flickr Creative Commons.